Supply chain trade finance: the next big thing

by Tim Nicolle, Founder & CEO, PrimaDollar

Supply chain trade finance is one of the biggest new developments for corporate treasurers and CFOs that has arrived in recent years - providing all the benefits of a supply chain finance programme but with all the reach and scope of the traditional banking trade finance products.

Supply chains - boring?

Supply chains never used to be that interesting – but then the pandemic came along. Suddenly, we have all realised how inter-connected companies and suppliers have become and also how much value is tied up in the efficient working of these relationships.

How international suppliers have been paid and financed has changed little over the years - even going back centuries. Traditional banking trade finance products have played their part, albeit with a much-declining market share in recent years, and innovations in supply chain finance have not been able to penetrate the cross-border world in any material way.

Trade finance, however provided, solves the collateral gap between the buyer and his exporting suppliers. The exporter ships his goods and trade finance is used to pay him at shipment. The buyer pays later. This is what both parties want, and it neatly avoids the buyer-side risk of non-payment having to be priced and accepted by supplier-side funders.

Source: PrimaDollar

In these more troubled times, Asian supply chains, in particular, are suffering a major liquidity problem. Several factors have caused this. In the first part of the year, many buyers cancelled orders that were already in production. After a period of reduced activity, new business is now returning, but many buyers are now asking for open account credit terms.

Supply chain trade finance has appeared at exactly the right time, providing all the savings and convenience of a supply chain finance programme, but run on platforms that are specifically designed for the international supply chain.

Is supply chain finance a good thing?

Significant cost savings are delivered by simplifying how suppliers are paid and getting them paid early. Getting payments delivered to suppliers early and in a standardised way results in an efficient cost of money in the supply chain. Every dollar of cost in the supply chain drives up the intake price for the buyer, and the buyer’s cost of money is usually significantly lower than the supplier’s cost of money. To put it simply, using the buyer’s credit to get cash into the supply chain as early as possible saves money. Additionally, supply chain finance programmes are convenient and simple ways to manage payments.

The two main benefits of supply chain finance are: (i) a simple and standard process to fund and pay suppliers, combined with (ii) early payment. Of course, there are the accounting questions as to whether supply chain finance provided to suppliers is truly trade credit or whether it has become a short term loan to the buyer, but this does not negate the financial benefits of standardisation and early payment. Whichever way the accountants decide to go, getting early payments out to suppliers and standardising the approach saves money.

Why does early payment to suppliers save money?

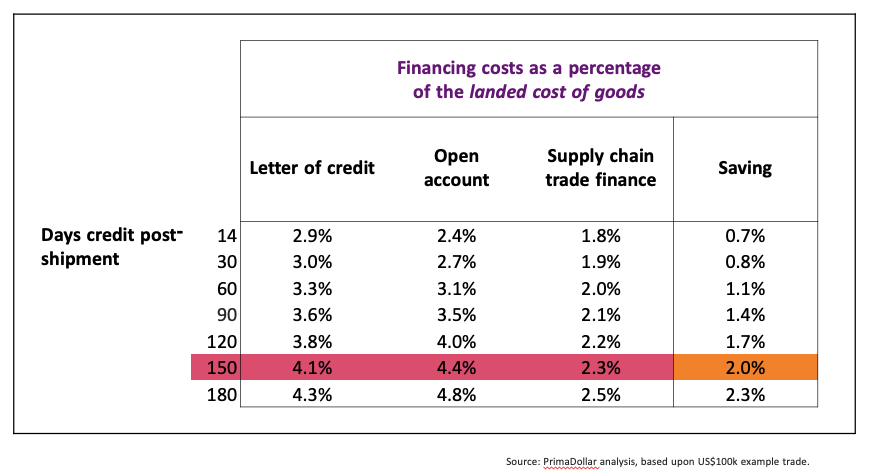

In the end, the buyer pays all the bills involved in the supply chain. This simple premise is important to keep in sight as negotiations are conducted with suppliers. No sustainable supply chain can operate at a loss, as the supplier will go out of business. Every dollar of the cost that sits on the shoulders of the suppliers will, in the end, be included in the landed cost of goods that the buyer pays. The greater the costs in the supply chain, the higher the landed price of goods that the buyer pays. Financing costs are a material part of the overall expense of the supply chain.

Early payments to suppliers, therefore, must make sense when the buyer has a lower funding cost and better access to finance than the supplier. But there is also another more important dynamic that is at work - risk allocation and the pricing of risk.

Source: PrimaDollar

In any supply chain, there is a risk that the supplier does not supply and a risk that the buyer does not pay. As a general principle, these risks are best managed locally to each party. In other words, the risks that the supplier does not supply can best be addressed and financed by the supplier’s local funders, while the risk that the buyer does not pay can best be addressed and financed by the buyer’s local funders.

Criss-crossing this simple equation results in the wrong risks being held by the wrong people, and directly results in higher charges. This is the principle that underlines the traditional bank trade finance model and the correspondent banking approach that we all know from documentary credits (the letter of credit). The buyer bank takes the buyer risks; the supplier bank takes the supplier risks. They are both best placed to know their own counterparties and to recover their positions if something goes wrong.

This crisscrossing is much less costly when suppliers and buyers are in the same country or nearby. It is much easier for supplier-side funders to understand the buyer-side risk and potentially lay off the risk. Moreover, there is much less time involved between shipment and delivery.

However, it is a big issue in international supply chains, particularly between Asia and Europe, and between Asia and the US. With long shipment times and distant buyers, it becomes essential to ensure that the supplier-side funding only runs up to shipment, and the buyer-side funding takes over from there. If the supplier gets paid at shipment, the supplier-side risk is not contaminated with the buyer-side risk. It becomes significantly easier and cheaper to finance in the supplier local market. The key point is that the supplier's local bank should not end up being exposed to the risk that the buyer does not pay, particularly if the buyer is far away.

The best way to do that is to get the supplier paid at shipment.

This is the main reason why 'open account' and deferred payment trades, where the supplier ships and the buyer is trusted to pay later, are inefficient from a financing point of view. The supplier and, more importantly, the supplier's local bank are not the best people to price and finance the risk of potential non-payment by the buyer later.

Why did open account and deferred payment become the standard for buyers?

This is an interesting question, and there may well be disagreement among different commentators. One widely-expressed view is that the practice emerged due to how China developed its global lead in manufactured products.

Over sixty years ago, most products were made locally to a buyer. With the invention of the container, improvements in international travel, and better communications, manufacturing moved east to China and other countries in South and East Asia. The Chinese developed a system that enabled suppliers to ship and get paid later.

Source: PrimaDollar

Chinese factories were empowered to offer trade credit themselves via three factors:

First, there was the very successful development of Sinosure, the Chinese state-owned export credit insurer. Sinosure credit insurance was made generally available to any exporter and typically covered pretty much any importer. Their main sanction for non-payment was to ban an importer from trading with Chinese companies again, which proved to be a serious threat for many buyers. Credit losses, if they ever came, were socialised by the government, so individual factories were not exposed. This was an ingenious system, which enabled Chinese factories to absorb the financial cost of the shipping times for goods and back their products with confident 'pay me later' terms.

The second development was in the banking system itself, which was, and still is, substantially state-controlled. The regulatory capital treatment of export credit loans was very favourable, which meant that banks were incentivised to discount international trade receivables on their balance sheets; this kept the local financing costs low.

The third factor was that most factories were “SOE” - state-owned enterprises.

With losses socialised, banks set up to provide trade credit. With factories largely being state-controlled, international buyers became hooked on the principle that they could demand credit from their suppliers, and that this was an efficient model. At the time, the buyers were right - the Chinese system was efficient.

What’s changing now that makes open account expensive?

Changes in China and also changes in the way that supply chains operate mean that open account with deferred payment has become expensive.

Many supply chains have been moving away from China, as other South and East Asian countries have built manufacturing capacity. Outside China, banking systems operate along more conventional lines, where local banks are cautious, and export trade credit insurance is only available on market terms. In China itself, the favourable capital treatment on export trade credit for banks fell away around 10 years ago, and many suppliers in China are now private companies and not state-owned enterprises. Moreover, the threat to buyers of being banned from China, which supported the Sinosure model, is no longer the comprehensive threat that it once was, now there are alternative suppliers across South and East Asia for most products.

On top of this, we now face the challenge of the pandemic. While not universally the case, many suppliers have found their buyers to be less reliable than expected. As lockdowns hit in the first half of 2020, many buyers walked away from orders - sometimes even after orders had shipped. This has materially affected confidence on the supplier side, and particularly in the local banking communities. This is driving up the cost and reducing the availability of pre-shipment finance if there is no letter of credit or agreement that the buyer will pay at shipment.

Exporting suppliers need to be paid at shipment.

Buyers that operate with open account and deferred payment terms can end up adding several financial costs into their supply chains. These are costs that, in the end, the buyer will pay in the landed price of goods.

The two main drivers are: (i) buyers usually have cheaper money than their suppliers, but more importantly (ii) suppliers and their local banks cannot easily assess the risk of later non-payment by the buyer, or they over-estimate this risk and this cascades into more expensive and more limited local pre-shipment financing that then extends for the deferred credit period.

The most efficient system is one that gets exporters paid at shipment. This ensures that there is no criss-cross in the risk allocation between the supplier universe (from purchase order through making and up to shipment) and the buyer universe (from shipment through delivery and up to payment). This is what the traditional banking trade finance products, like the letter of credit, have always achieved.

Is supply chain finance the answer?

The obvious way for large corporates to get early payment out to exporting suppliers is to use supply chain finance. This avoids the need for complex and expensive banking trade finance products, like the letter of credit.

However, a recent PwC survey of corporate treasures and CFOs found that supply chain finance programmes served only 15% of suppliers. In the same survey, PwC found that 84% of corporates would like to expand their supply chain finance programmes. It is not that suppliers do not want early payments; it is that supply chain finance programmes are limited in scope because of the way that they work.

The typical operation of supply chain finance is as follows. Eligible suppliers are moved to deferred payment terms (such as 120 days, for example), and a technology platform is implemented to connect the buyer and the eligible suppliers to one or more banks. As suppliers deliver goods to the buyer, the goods are checked, and then invoices are approved for early payment. On the platform, suppliers can see the invoices that get approved and request early payments; the payments are immediately made to them by the one or more banks. The buyer then pays later.

Source: PrimaDollar

There are two main limitations on who can get early payments. First, the bank typically has to adopt each supplier, individually, as a client. This is because the bank is providing an export trade credit facility as requested by suppliers, based upon the strength of the buyer’s credit. This is why supply chain finance is usually shown as trade credit in the books of the buyer. Second, the buyer has to be able to approve the invoices early, but if the buyer approves invoices too early, there is a material risk of overpaying suppliers.

These two limitations have meant that supply chain finance is typically limited to larger suppliers located in easy jurisdictions, and early payments are made after delivery and not before. These limitations are caused by the economic cost of compliance on the part of the bankers and risk of over-payment on the part of the buyer. Supply chain finance is a good thing and creates direct cost savings for large corporates, but generally does not tick the box for cross-border trades because payments to suppliers come too late and because funders do not want to handle the compliance issues involved.

Source: PrimaDollar

Therefore, supply chain finance is not an effective model to get early payment out to exporting suppliers. What we are all looking for is a system that can include all the suppliers, and which can get the payment at shipment without having to wait for delivery. What is needed is a trade finance product, not an invoice finance product.

Supply chain trade finance is the answer.

Supply chain trade finance (or SC-TF) allows the CFO or corporate treasurer to standardise payment terms to international suppliers globally. This is because all suppliers can be eligible for early payments, both economically and practically. This eligibility results from how an SC-TF programme works, since it is quite different from traditional supply chain finance. It is a trade finance product and not an invoice finance product.

The main difference between SCF and SC-TF is practical. SC-TF works backwards from a data processing perspective.

Source: PrimaDollar

Instead of being fed approved invoices from a large corporate accounting system, an SC-TF platform harvests all the information needed to operate from the supply chain itself. Individual exporters log into the platform and upload their invoices, shipping documents, inspection reports and the whole variety of other items that are needed to verify that they have done their job and put the right goods on the boat. This information is analysed and tidily presented to the CFO’s team at the buyer, who can then decide on payment. If payment is agreed, it is the platform that makes the payment, and not the funder.

This last step is important for two reasons. First, SC-TF structures typically work with staged payments - exporting suppliers are not paid 100% immediately. Still, they receive some funds at shipment (70-90%) based upon tariffs set by the buyer, some funds at delivery and some funds later on the invoice due date. This more complex payment structure enables the buyer to manage the risk of over-paying suppliers and to deal with offsets and credit notes efficiently. Second, if the platform can make the payments, then the funder no longer needs to onboard the supplier.

Source: PrimaDollar

Of course, there is still a compliance process in place as the platform has the same compliance obligation itself, but the unit cost of a fintech for the compliance process is much lower. Moreover, the platform has all the information needed to do trade finance compliance properly since the shipping documents are there in the system and attached to each trade. Sanction checks on the transaction, the vessel and the routing can be done easily within the platform itself.

What are the differences then between SCF and SC-TF?

Invoice finance (e.g., SCF) and trade finance (e.g., SC-TF) are different products delivering the same early payment outcome but for different populations of suppliers.

To finance an invoice, we need to assess is the chances of the buyer not paying, either because of an offset (i.e., a credit note or dilution) or because they cannot pay due to a credit problem. In compliance terms, it is a relatively simple equation as well, provided the goods are delivered, and we are simply dealing with the confirmed supply of accepted goods to the buyer.

Source: PrimaDollar

Trade finance is necessarily aimed at financing goods on the water - the period between shipment and delivery - with the potential for a further credit period post-delivery to be added on. Over the centuries, bankers and merchants defined a strong and proven methodology to do this safely. This is why trade finance is often called a 'documentary credit'. Since the goods were not available to evidence the performance of the supplier, documents were substituted. The documents involved are generated by third parties, like a freight forwarder or a shipping line, independent inspectors, local authorities, customs officials, local banks and so on. Trade finance needs a lot more information to make it work, and it does work. A traditional bank letter of credit definitely delivers the simple result that everyone wants, which is getting the supplier paid at shipment and allowing the buyer to pay later. But the reality is that no one, today, enjoys the journey - and LCs are not the way forward.

The hard reality is that getting early payments out to international exporting suppliers requires a different approach that embraces the old world of trade finance and all the documents needed, but moves the process into the new, platform-based world of supply chain finance. This is best achieved with the upside-down model that has been developed in the new breed of supply chain trade finance platform.

What is the IT cost of adding an SC-TF programme?

As many corporate treasurers and CFOs know well, touching the accounting system or ERP environment inevitably brings a multi-million dollar cost as consultants and engineers enhance and amend functionality to service new requirements. The good news with supply chain trade finance is that there is no IT project. All the data is surfaced from the supply chain itself, and there is no mandatory interface needed to the buyer’s ERP. This means that SC-TF platforms are truly turnkey solutions. Just plugin and go.

Moreover, SC-TF co-exists happily alongside existing supply chain trade finance platforms. While it would always be annoying to have parallel systems, supply chains can be neatly divided between suppliers who need an invoice finance solution (SCF) and suppliers who need a trade finance solution (SC-TF). As PwC found in its survey of corporate treasurers and CFOs, over 60% of large corporates already have more than one supply chain finance solution in place anyway, and experience of the existing family of SCF solutions tells us that a one-size, fits-all approach is not the most efficient way forward.

What is the bottom line?

The industry consensus is that there are large cost savings available to corporates that take control over how international suppliers are funded and paid. This is irrespective of whether suppliers are on open account, LC, down-payment or TT. Integrating payables and logistics processes at the buyer-end of the supply chain, and then using the resulting data flow to standardise and then drive early payments out to exporting suppliers can reduce the landed cost of goods by 2% or more. These are material savings:

Who needs supply chain trade finance?

Most organisations have supply chains that span domestic and international, nearby and distant. SC-TF should only be used for the more distant international suppliers who need a trade finance solution and where the benefit of getting early payment at shipment is significant. Typical SC-TF clients are retailers and manufacturers whose supply chain extends out into the emerging markets.

Where can I find out more?

The first and largest provider of supply chain trade finance solutions is the UK trade finance fintech, PrimaDollar (www.primadollar.com).

Elsewhere, the SCF industry giants, such as Prime Revenue (www.primerevenue.com), Taulia (www.taulia.com) and the largest player in providing supply chain finance (Greensill, www.greensill.com) are all turning their attention to supply chain trade finance as the next big thing in their worlds. Initiatives are emerging in this area across the industry.

Like this item? Get our Weekly Update newsletter. Subscribe today